The Backstory

A few years ago, I was commissioned by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to provide some new photographs of some the machinery and processes used in radiation treatment of various cancers. I had never seen these machines face-to-face, but I knew what they looked like and a few searches through Corbis Images gave me some ideas of how these machines might look best. However, NCI didn’t just want the machines, they wanted people in the shot to provide a narrative to the scenes I would be depicting. So, weeks of meetings and planning kicked-in before I was even able to do a location scout of the facility.

Getting on-site was a challenge because it was an active treatment center and the meetings and shoots had to revolve around the doctors’ and staff’s ever-changing schedule. Meeting with the physicians, nurses, and technicians was crucial in order to make sure we were being authentic and following medical protocol since NCI’s audience was not only the general public, but also doctors and researchers. Little details like wearing gloves, holding an instrument properly, etc. goes a long way in projecting credibility and professionalism. The team — the art-director, journalist, and myself — toured the various machines and got brief demos and explanations, helping us plan the shoot efficiently.

Being efficient and having a small footprint was really important on this shoot because it was an active medical facility where our shoot was a distant second-place to serving the patients at the National Institutes of Health’s Clinical Center. We needed to be able to break-down quickly if a room needed to be used. So, I decided to use speedlights rather than larger studio strobes. This provided me with the power and portability I needed along with wireless control, perfect for a room with a large obstruction in the middle of it (more on that later). Aside from the scheduling considerations, we also had to deal with HIPPA concerns if we were to use any patients. So, to get around that additional layer of paperwork and variable, the art-director volunteered to be the patient, being restrained in a custom, form-fitted headmask.

For over 3 hours straight.

It didn’t take 3 hours to do this one shot — we did a whole bunch in order to give a good visual narrative of obtaining a clear CT scan of the brain — but she was strapped to the bed for that long. Real trooper.

The Setup

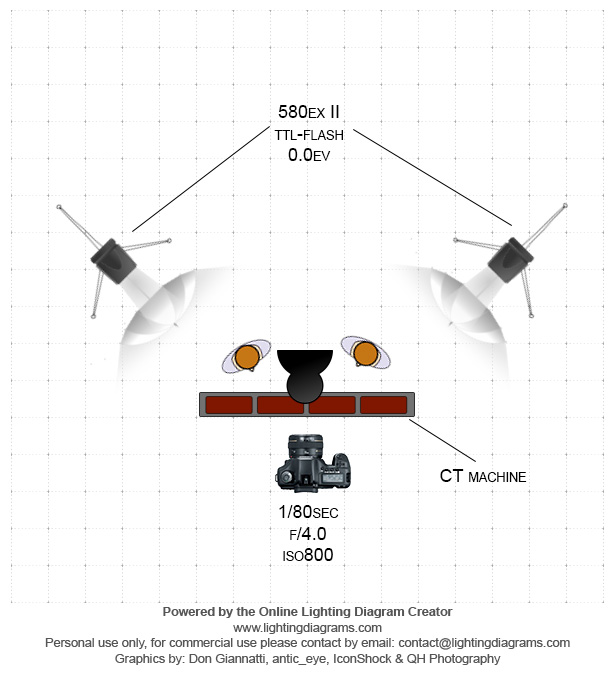

This shot was pretty simple, using only 3 speedlights, 2 shoot-thru umbrellas on stands, and a camera with a wide-angle lens. I placed a slaved flash with each umbrella to the rear flanks of the doctors to provide both a rim and key light while I shot from the opposite side of the machine. I decided to use TTL-controlled flash because it was quick and I could make adjustments from my position by simply adjusting the flash compensation. Here is the setup:

The position of the lights was also dictated by the glass windows of the computer observation room in the background. I didn’t want the umbrellas to show up. After the position was down, I adjusted my ISO up to 800 so the ambient could mix-in and give me more fill and help the lighting feel a little more natural.

Shooting the CT Scan Machine

So, once I got my ambient where I liked it, I decided to add the strobes. They didn’t fire.

I peeked around the side of the CT scan machine. The slaved flashes are on and properly set. Fire again. Nada.

After two or three misfires, I thought I would need to trash the shot. The TTL pre-flashes weren’t reaching the other flashes. The CT scan machine was blocking the light.

Pointed the flash up. Nope.

Pointed it left. Nope. Pointed it right. Nope.

I really wanted this photo and there had to be a way to make it work, but it just wasn’t working with the line-of-sight system I had. Until I looked behind me. And then I remembered Joe McNally.

Just when you think all is lost, you get tossed a little life-preserver in the shape of a large, shiny stainless steel cabinet.

I swiveled that master 580EX II to the rear, aiming it at 45° upward towards this ad hoc reflector for my wireless signal. BOOM!

Two or three adjustments in the models and we end up with this: